(cuttingedge)

By Peter Chilson

|

Photo

by Ken Redding |

Nineteen feet of snow fell on northern Idaho in the winter of 1996, resulting in an unusual slaughter of wildlife. Heavy snows in an area known as the McArthur Lake wildlife corridor forced deer, elk, and moose down from the mountains and onto U.S. Route 95. Although the animals managed to cross the two-foot snowbanks without much problem, when they reached the icy road they became disoriented and vulnerable. Forest Service and Idaho Transportation Department officials estimate that at least 200 deer, along with a handful of moose and elk, died after being hit by cars. As Forest Service biologist Sandra Jacobson says, "They tend to concentrate in the lower elevations . . . the deeper the snow, the lower they try to range. The death rates show that this is winter range."

After nearly four years of talks, Jacobson has convinced Idaho highway engineers to include three wildlife underpasses in phase one of a 17-mile reconstruction project in another section on the northernmost stretch of Route 95. The concrete underpasses—13 feet high, 23 feet wide, and 80 feet long—cost $400,000 apiece, not including fencing to keep the animals off the road and to guide them to the structures. Jacobson, who worked on wildlife and transportation issues for the national forests in the Idaho panhandle (she now keeps an eye on the Route 95 project from her new job as a biologist with the Forest Service Pacific Southwest Research Station in Arcata, California), expects that "punching holes" in Route 95 will make it safer for both wildlife and drivers.

Don Davis, an engineer and leader of the highway project,

expects work to begin this summer. He concedes that road designers have

long been guilty of laying down asphalt with no consideration for beings

other than humans. But now, he says, engineers are under more pressure

from federal agencies like the U.S. Forest Service to change their ways.

"We need to show more sensitivity to the surrounding area rather

than having a sterile highway going down the middle," Davis says.

Every year, collisions with deer alone cause millions of dollars in

vehicle damage and 12,000 human injuries nationwide, according to the

American Automobile Association. The impact on wildlife is, if anything,

harsher. The nation's 4 million miles of roads fragment habitat and

threaten species. For example, roads have helped reduce the population

of the ocelot, an extremely endangered cat native to the Southwest,

to 80 individuals. Roads have devastated amphibian populations and the

wetlands where they live, including most of the habitat of California's

red-legged frog.

Wildlife crossings have proven successful in Europe, where the loss of wildlife and habitat is a centuries-old issue. Europeans have been trying to protect animals from roads since the 1950s, and they are now sharing what they've learned with U.S. biologists and engineers. Richard Foreman, a landscape ecologist at Harvard University, says the country needs a broad national policy covering roads and the environment. "The overall goal of transportation is safe and efficient mobility, and the secondary goal is to minimize the environmental devastation," he says. "[The United States] has done the first brilliantly and the second very poorly."

Since the early 1980s hundreds of millions of state and federal dollars have gone into improving roads for wildlife, but in piecemeal fashion, with no broad policy to define how and where to spend the money. The Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) doesn't track the spending or the number of undertakings, although officials say that at least 15 current road projects around the country include wildlife protection in their designs.

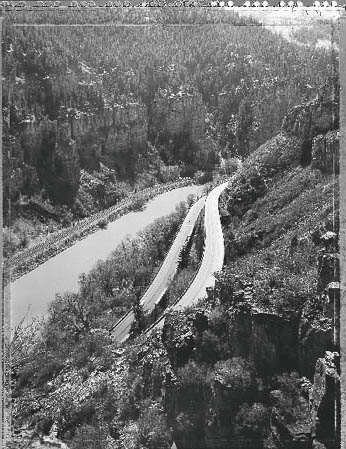

One of the biggest projects to be completed was the $498 million reconstruction of Interstate 70 through Colorado's Glenwood Canyon, along the Colorado River. This 12-mile stretch of road had been two lanes of tortuous and dangerous driving, but in 1984 work began on a terraced four-lane structure, the westbound lanes above the eastbound lanes in a system of 40 bridges and viaducts. The aim was to build a wider and safer road while preserving the canyon's geology and riparian habitat. Guardrails were designed so that the natural slopes reached their tops, creating a dropoff that kept bighorn sheep and other ungulates off the road. The native sheep had been evacuated from the canyon in the early 1970s to save them from death on the highway, but once the road was rebuilt, in 1992, the state approved their return.

Most wildlife-crossing structures, however, were actually built for some other purpose. In California's San Bernardino County, for example, biologists discovered that certain desert tortoises were profiting from storm-water culverts. From 1994 to 1999 the biologists outfitted 200 desert tortoises—a threatened species in California—with microchip tracking devices to study their movements along state Route 58. A dozen of the creatures were dying each year, imperiling a species with a long lifespan—20 to 25 years—but a low reproductive rate. The researchers found that some tortoises were crossing through culverts beneath the highway, a journey that averaged seven hours. So the state put up fences to keep the tortoises off the road and guide them to the culverts. Tortoise deaths on the highway fell by 93 percent over four years, says William Boarman, the U.S. Geological Survey biologist who led the study. "That's a reduced mortality just because of fencing."

Thousands of wildlife crossings now exist in the United States, from culverts to bridges and elevated roadways. Besides desert tortoises in California, they protect mountain goats in Montana, spotted salamanders in Massachusetts, steelhead trout in Oregon, bighorn sheep in Colorado, and panthers in Florida. In western Montana, plans to rebuild a 55-mile section of U.S. Route 93 include 42 crossing structures, such as culverts for ungulates, a wildlife overpass, and nearly 15 miles of fencing to keep the animals off the road surface. Work on the $125 million project will begin next year.

Many biologists are less concerned with wildlife dying on highways than with how roads chew up habitat and isolate species. Terry Gilbert, a biologist with the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission, has helped put in about a dozen crossing structures for Florida panthers and black bears. Still, he says, the structures can't work unless the roadside habitat is also protected. "If you expand a road and its capacity to carry people," says Gilbert, "you create an excellent climate for commercial development and you essentially fragment that habitat. [In Florida] we're trying to acquire large blocks of habitat to create large contiguous core areas."

A clutter of commercial and residential development is just the challenge Sandra Jacobson faced with Idaho's McArthur Lake corridor, a glacial plain between the Selkirk Mountains to the west and the Cabinet Mountains to the east. The pale asphalt of Route 95 runs north to south like a dirty shoelace through this flat, open land—a natural travel path for black bears, deer, elk, and moose moving between mountain habitats.

Unfortunately, the animals share the corridor with 4,600 cars and trucks daily. To further complicate matters, wildlife must also contend with 40 trains a day, since the corridor also contains the Union Pacific and Burlington Northern Santa Fe railways. Private land—full of roads, driveways, fencing, cars, and buildings—extends a mile or more on either side of the highway before bumping up against national forest land.

For years Jacobson had been pushing for the construction of three underpasses on this 11-mile section of highway. Just before she transferred to California last summer, Jacobson's lobbying for road improvements in the corridor began to pay off. She secured a $300,000 FHWA grant to build a wildlife underpass on Route 95 near the McArthur Lake corridor. The Forest Service is now working with businesses along the road, and with state agencies and environmental groups—including the Kootenai Tribe of Idaho, the Idaho Department of Fish and Game, and American Wildlands—to gather information about heavily traveled animal crossings. Meanwhile, the Idaho Transportation Department has announced it will straighten out a long, dangerous curve near the lake where vehicle-wildlife collisions are especially common.

Tom Perlic, regional representative for American Wildlands, has high hopes for road improvements in the McArthur Lake corridor. "This is a chance for a bunch of groups to sit down and try to manage an area and do some good. That bodes well for the future."

Still, no one can be sure how a particular animal population

will react to a wildlife crossing. The best biologists can do, Jacobson

concedes, is to study travel corridors and make predictions.

Some studies show that it takes years for animals to adjust to using

crossing structures. In the 1980s, 11 underpasses were built on the

Trans-Canada Highway through Banff National Park. Park wardens had confirmed

that elk and deer used the underpasses, but it wasn't until a research

team began a monitoring effort in the fall of 1996 that large carnivores

such as gray wolves, cougars, and black and grizzly bears were documented

making use of the crossings.

"It takes four years or longer for individuals to adapt," says Parks Canada's Tony Clevenger, the lead biologist on the long-term study of the Banff project. He and his team found that since the first underpasses were built and new fencing was added in 1997 (there are now 24 structures), roadkill has dropped 80 percent.

Nonetheless, poor understanding of animal behavior dooms some projects. "A lot of problems stem from sticking a small culvert in a road and hoping for the best," says Bill Ruediger, a Forest Service ecologist and an authority on transportation ecology. There are too many unknowns about animal behavior, he adds, which means that trial and error must be part of planning for crossing structures.

Richard Foreman, the Harvard landscape ecologist, points to Holland

as a model for what the United States should do to protect wildlife

and habitat from roads. In the 1980s the Dutch parliament required the

Ministry of Transport to map the national ecological network, including

all large green areas, to reveal where roads posed the greatest threats

to wildlife.

But Holland is roughly the size of Massachusetts, with less than 100,000 miles of roads. The United States, by contrast, has a vastly more complex ecology and transport system. The FHWA's Fred Bank, an ecologist, says the country is slowly moving toward the Dutch model. Bank is part of an FHWA team holding workshops around the country to show state and local officials how to use federal aid to benefit wildlife. The agency is also funding a National Academy of Sciences study on the impact of highways on ecosystems.

"That's how a policy is going to happen," says Bank, "by education, encouragement, and sharing the benefits."

Meanwhile, in Idaho, Tom Perlic has picked up Jacobson's work of building the case for more underpasses through the McArthur Lake corridor. With Jacobson's help, he has assembled volunteers and road-maintenance workers to monitor and count roadkill, and both Jacobson and Perlic are looking for project money from government and private sources.

"What we really need," Jacobson says, "is something akin to the interstate highway system—a highway system for critters."

Peter Chilson teaches creative writing at Washington

State University. He has written for The American Scholar and

North American Review.

© 2003 NASI

For more information on Federal Highway

Administration (FHWA) activities and on workshops about roads and

wildlife, visit the web site of the International Conference on

Ecology and Transportation (http://www.icoet.net/).

Also visit the FHWA's "Critter Crossings" web site, at

www.fhwa.dot.gov/environment/wildlifecrossings/.

Additionally, Sandra Jacobson has spearheaded the design of www.wildlifecrossings.info/,

a Forest Service web site that monitors the effectiveness of wildlife-protection

efforts on highways across the country. To learn about additional

studies on roads and wildlife and about restoration practices, read

Richard Foreman's Road Ecology (Island Press, 2002). |